The early days of airmail services in the United States marked a significant milestone in the history of mail delivery.

With the advent of airplanes, the United States Postal Service began transporting letters and packages through the skies, revolutionizing the speed and efficiency of mail delivery.

These rare and historic photographs capture the planes, pilots, and support staff that made airmail services possible. F

rom the early biplanes that were used to carry mail, to the larger and more advanced aircraft that followed, these images provide a fascinating look at the evolution of airmail technology.

One notable aspect of these vintage photos is the sense of adventure and excitement that they convey. For many of the pilots and support staff involved in airmail services, this was a new and thrilling experience that required courage, skill, and dedication.

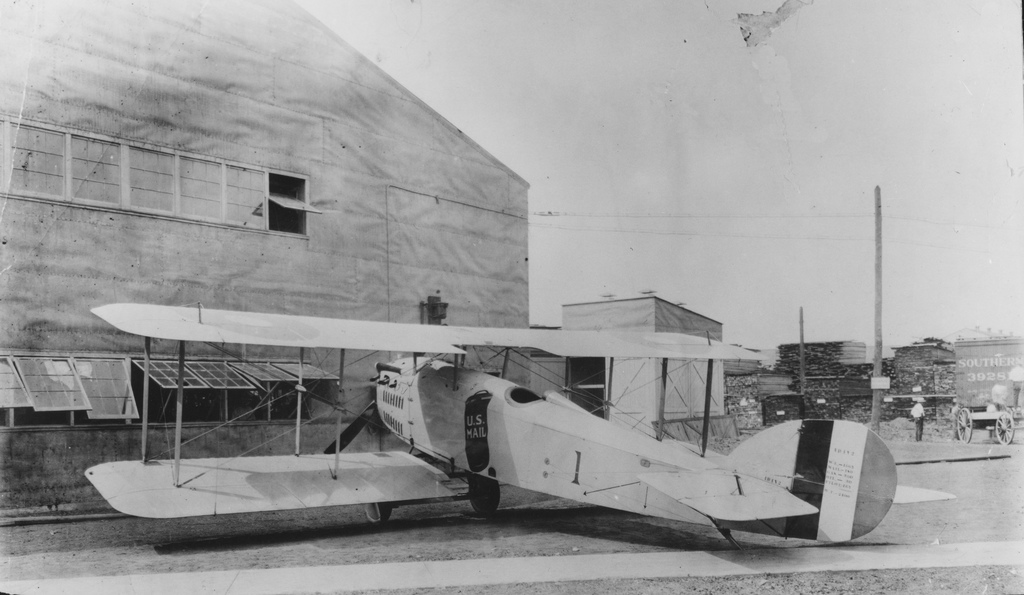

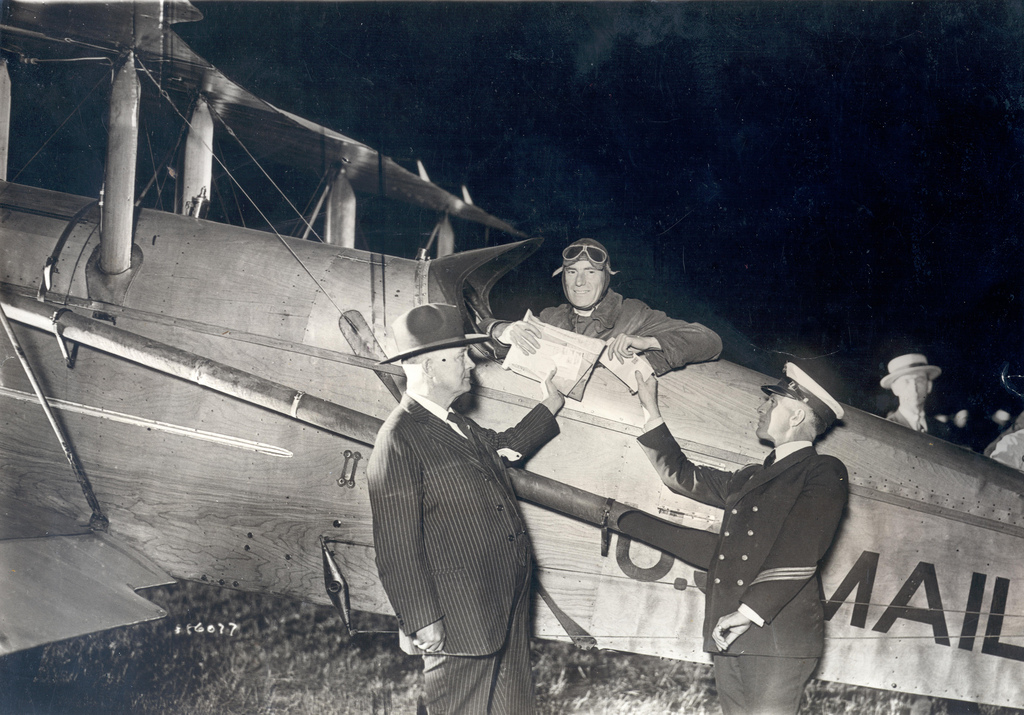

First day of the U.S airmail service, May 15, 1918

On February 18, 1911, Fred Wiseman transported two letters to Santa Rosa, California Postmaster H.l. Tripp from Petaluma, California Postmaster John Olmsted.

When the letters arrived, Fred became the pilot who carried the first airmail sanctioned by a U.S. postal authority.

The first scheduled U.S. Air Mail service began on May 15, 1918, using six converted United States Army Air Service Curtiss JN-4HM “Jenny” biplanes flown by Army pilots under the command of Major Reuben H. Fleet and operating on a route between Washington, D.C. (Washington Polo Grounds) and New York City (Belmont Park) with an intermediate stop in Philadelphia (Bustleton Field).

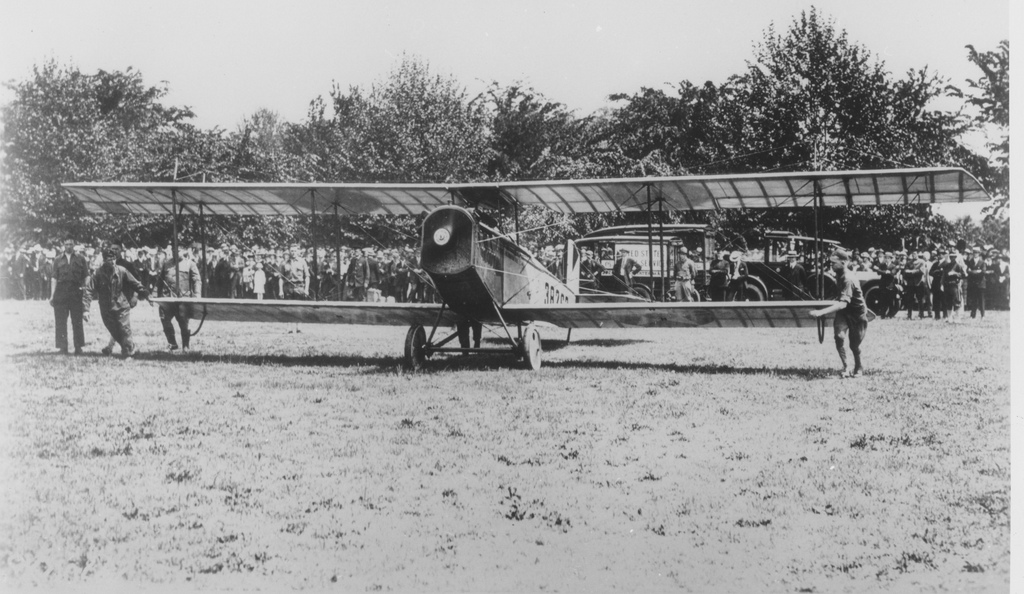

JR-1B mail airplane designed by the Standard Aircraft Corporation, 31 Dec. 1918

These early mail planes had no reliable instruments, radios, or other navigational aids. Pilots navigated using landmarks and dead reckoning.

Forced landings occurred frequently due to bad weather, but fatalities in the early months were rare, largely because of the planes’ small size, maneuverability, and slow landing speed.

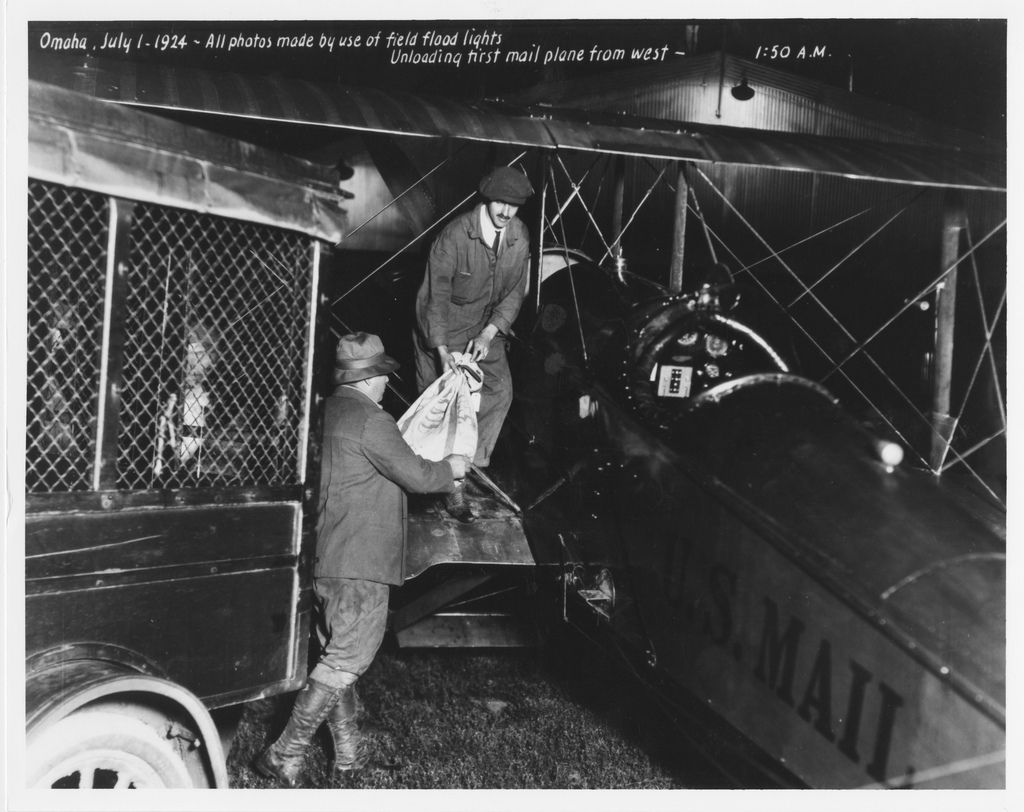

To better its delivery time on long hauls and entice the public to use airmail, the Department’s long-range plans called for a transcontinental air route from New York to San Francisco.

The first legs of this transcontinental route — from New York to Cleveland with a stop at Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, then from Cleveland to Chicago, with a stop at Bryan, Ohio — opened in 1919.

A third leg opened in 1920 from Chicago to Omaha, via Iowa City, and feeder lines were established from St. Louis and Minneapolis to Chicago.

The last transcontinental segment — from Omaha to San Francisco, via North Platte, Nebraska; Cheyenne, Rawlins, and Rock Springs in Wyoming; Salt Lake City, Utah; and Elko and Reno in Nevada — opened on September 8, 1920.

JR-1B mail airplane, 1918

Initially, mail was carried on trains at night and flown by day. Still, the service was 22 hours faster than the cross-country all-rail time.

In August 1920, the Department began installing radio stations at each airfield to provide pilots with current weather information.

By November, ten stations were operating, including two Navy stations. When airmail traffic permitted, other government departments used the radios for special messages, and the Department of Agriculture used the radios to transmit weather forecasts and stock market reports.

Loading airmail in New Brunswick, New Jersey, 1925

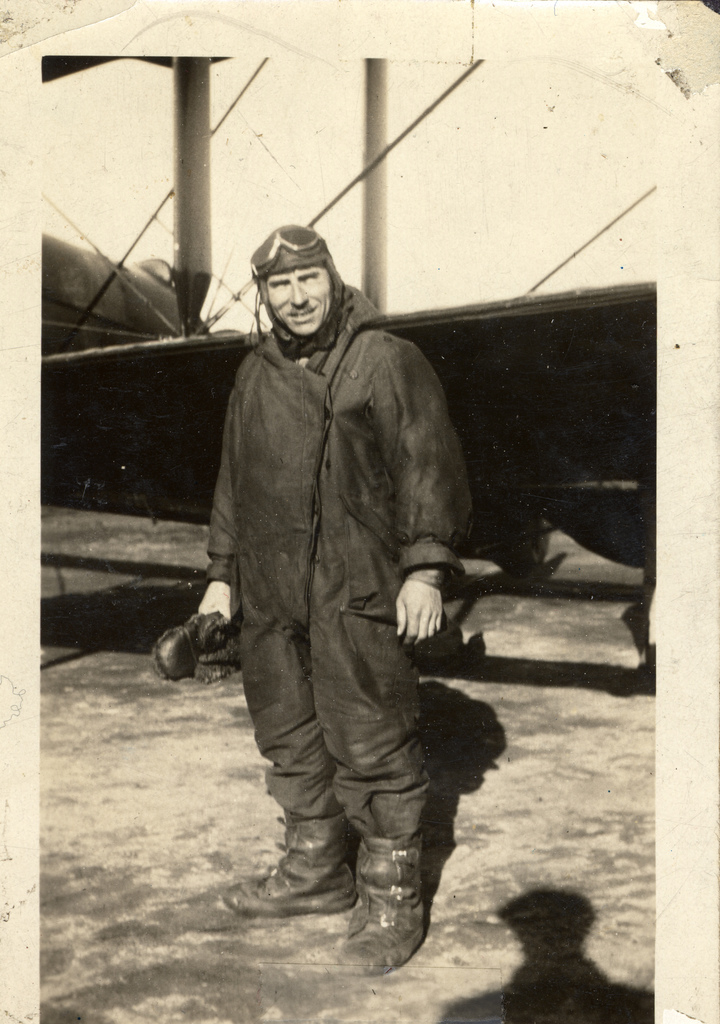

Pilots flew in open cockpits in all kinds of weather, in planes later described as “a nervous collection of whistling wires, of linen stretched over wooden ribs, all attached to a wheezy, water-cooled engine.”

A 1918 article titled “Practical Hints on Flying” advised pilots to “never forget that the engine may stop, and at all times keep this in mind.”

Unpredictable weather, unreliable equipment, and inexperience led to frequent crashes; 34 airmail pilots died from 1918 through 1927.

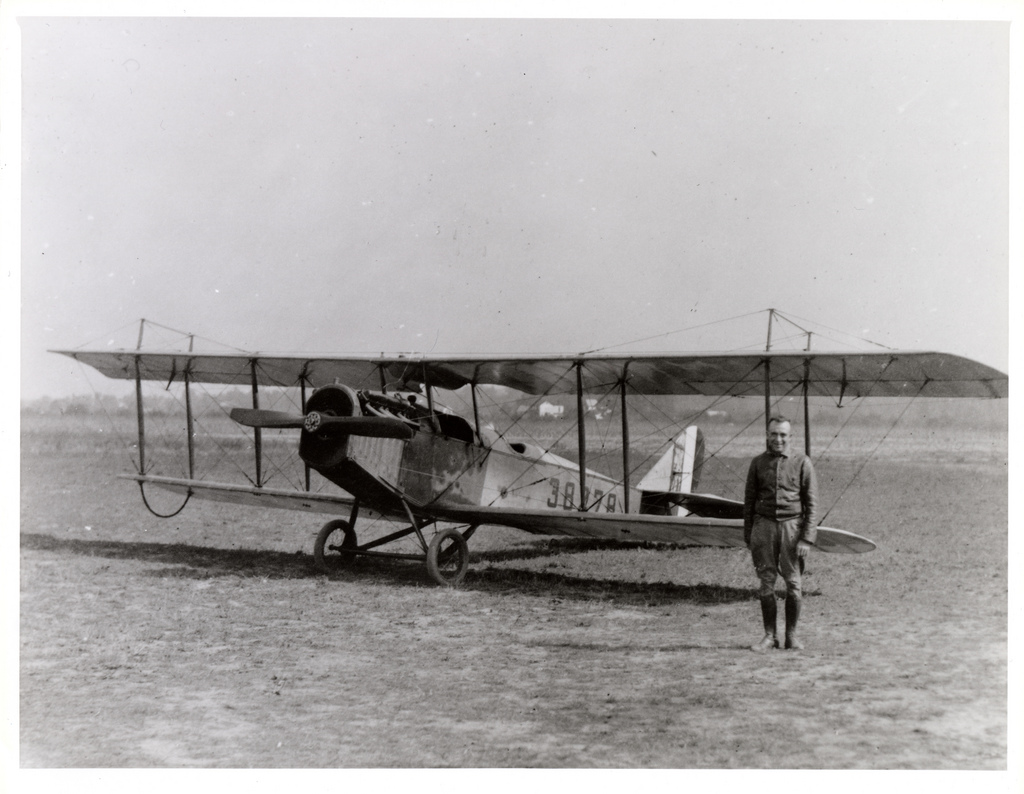

New York City postmaster Thomas G. Patten and airmail pilot Lt. Torrey Webb, 1918

The original air mail letter rate per ounce between any two points on the route when service began was 24 cents per ounce for which the first special-purpose U.S. air mail stamp (C-3) was issued on May 13, 1918.

The red and blue stamp’s vignette depicted Army JN-4 #38262, the aircraft that made the first airmail flight from Washington two days later, and the 24 cent fee it represented was apportioned at two cents for postage, 12 cents for air service, and 10 cents for Special Delivery.

On July 15 the rate was dropped to 16 cents for the first ounce and 6 cents for each additional ounce, and on December 15 the rate was dropped again to 6 cents per ounce when Special Delivery was made optional.

Pilot Eddie Gardner posing in front of an airmail plane, 1918

Pilot Eddie Gardner posing in front of an airmail plane, 1918The exclusive transportation of flown mails by government-operated aircraft came to an end in 1926 under the provisions of the “Kelly Act” which required the USPOD to transition to contracting with commercial air carriers to fly them over Contract Air Mail (CAM) routes to be established by the department.

During the first half of 1934, the U.S. Army Air Forces temporarily took over the routes—with disastrous results—when all CAM contracts were summarily canceled by President Franklin D. Roosevelt owing to the Air Mail scandal.

Domestic air mail became obsolete in 1975 as a distinct extra fee service, and international air mail in 1995, when the USPS began transporting all First Class long-distance intercity mail by air on a routine basis.

Unloading Airmail in Chicago, Illinois, 1921

Unloading Airmail in Omaha, Nebraska, July 1, 1924

A de Havilland airmail plane parked on unidentified airfield next to a U.S. mail truck, 1922

A modified de Havilland airmail plane with number #299, 1920

A U.S airmail plane on take off, 1918

Airmail loaded for pathfinding transcontinental flight, July 29, 1920

Airmail pilot E. Hamilton Lee, 1924

Airmail pilot Eddie Gardner and journal reporter Muriel Kelly, August 30, 1920

Airmail pilot Eddie Gardner, 1918

Airmail pilot Edward Killgore, 1918

Airmail pilot James Hill ready for transcontinental night flight, July 1, 1925

Airmail pilot Lloyd Bertaud and an unidentified individual, September 6, 1927

Airmail pilot Lt. James Edgerton and his young sister, May 18, 1918

Airmail pilot Paul Collins and bag of first overnight airmail, July 1, 1925

Airmail pilot William Fillmore, 1925

Airmail pilots Edison Mouton and Rexford Levisee, 1921

Airmail plane at Chicago, 31 Dec. 1920

Airmail planes at Elko, Nevada, 1920

Airmail planes at Omaha, Nebraska, 1920

Airmail planes at Omaha, Nebraska, 1924

Airmail planes at Reno, Nevada, 1920

An airmail plane in front of a hangar on the Omaha, Nebraska airmail field, 1927

Curtis JN-4H airmail plane taking off, 1918

(Photo credit: Smithsonian Institution / USPS / Wikimedia Commons).