Mining coal has always been a dangerous and challenging occupation, requiring workers to dig deep underground, often in cramped and dangerous conditions.

In this article, we present a collection of vintage photos that offer a glimpse into the daily struggles and hardships of coal miners in the early to the mid-20th century.

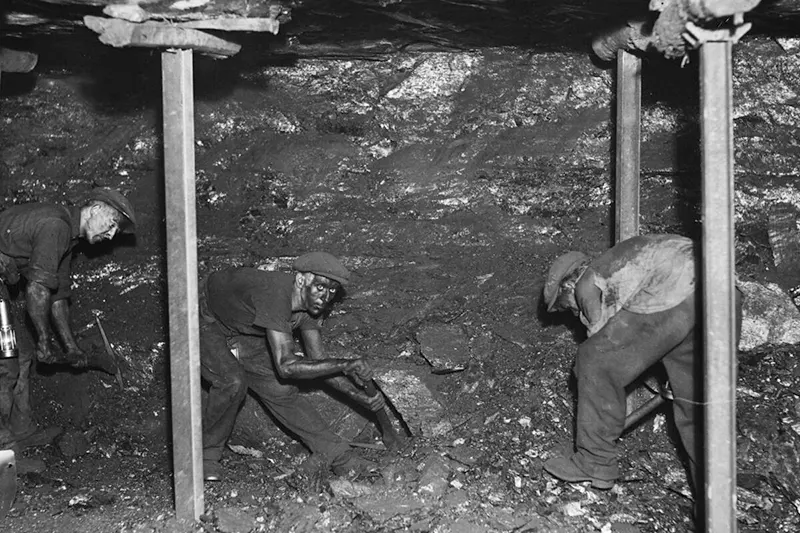

These photographs capture miners at work, as they use pickaxes, shovels, and other tools to extract coal from deep within the earth. One striking aspect of these old photos is the sheer physical effort that mining required.

The miners pictured are often covered in coal dust, their faces and clothing blackened by the work they do. The photos show them using all of their strength to move heavy carts of coal, often in cramped and poorly lit spaces.

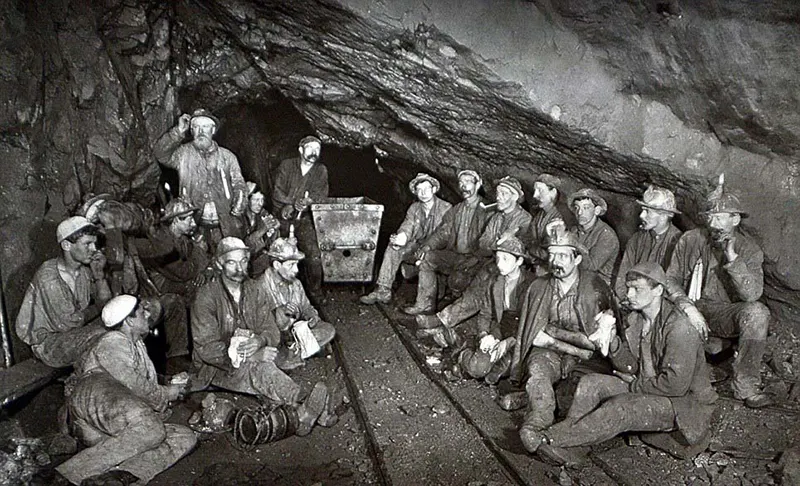

Another aspect of coal mining that is captured in these shots is the sense of community that existed among the miners.

Despite the difficult conditions they faced, the miners often worked together in teams to extract coal and support one another. This sense of camaraderie was essential for their survival, both in terms of physical safety and emotional well-being.

In many ways, these vintage photos offer a window into a bygone era, when coal mining was a way of life for millions of people around the world.

They serve as a reminder of the sacrifices that miners made to provide for their families and communities, often in the face of great danger and adversity.

A group of “pit boys” wait to go to work in the Sirland & Alfreton pits in Derbyshire, England, 1905.

The history of coal mining goes back thousands of years, with early mines documented in ancient China, the Roman Empire, and other early historical economies.

It became important in the Industrial Revolution of the 19th and 20th centuries, when it was primarily used to power steam engines, heat buildings and generate electricity.

Compared to wood fuels, coal yields a higher amount of energy per unit mass, specific energy or massic energy, and can often be obtained in areas where wood is not readily available.

Though it was used historically as a domestic fuel, coal is now used mostly in industry, especially in smelting and alloy production, as well as electricity generation.

Large-scale coal mining developed during the Industrial Revolution, and coal provided the main source of primary energy for industry and transportation in industrial areas from the 18th century to the 1950s.

Britain developed the main techniques of underground coal mining from the late 18th century onward, with further progress being driven by 19th-century and early 20th-century progress.

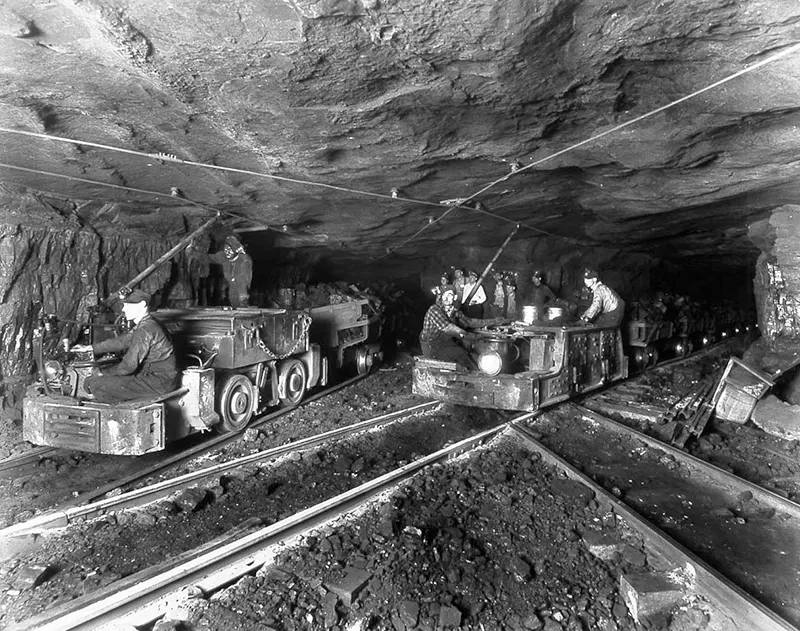

West Virginia coal mine, circa 1940.

The history of coal mining in the United States starts with the first commercial use in 1701, within the Manakin-Sabot area of Richmond, Virginia.

Coal was the dominant power source in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and although in rapid decline it remains a significant source of energy in 2023.

Anthracite (or “hard” coal), clean and smokeless, became the preferred fuel in cities, replacing wood by about 1850. Bituminous (or “soft coal”) mining came later. In the mid-century Pittsburgh was the principal market.

After 1850 soft coal, which is cheaper but dirtier, came into demand for railway locomotives and stationary steam engines, and was used to make coke for steel after 1870.

Total coal output soared until 1918; before 1890, it doubled every ten years, going from 8.4 million short tons in 1850 to 40 million in 1870, 270 million in 1900, and peaking at 680 million short tons in 1918.

New soft coal fields opened in Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, as well as West Virginia, Kentucky and Alabama. The Great Depression of the 1930s lowered the demand to 360 million short tons (330 Mt) in 1932.

10 Ton Electric Mine Locomotive, Sloan Mine, Scranton, Pennsylvania. 1910.

Under John L. Lewis, the United Mine Workers (UMW) became the dominant force in the coal fields in the 1930s and 1940s, producing high wages and benefits.

In 1914 at the peak there were 180,000 anthracite miners; by 1970 only 6,000 remained. At the same time steam engines were phased out in railways and factories, and bituminous coal was used primarily for the generation of electricity.

Employment in bituminous peaked at 705,000 men in 1923, falling to 140,000 by 1970 and 70,000 in 2003. UMW membership among active miners fell from 160,000 in 1980 to only 16,000 in 2005, as coal mining became more mechanized and non-union miners predominated in the new coal fields.

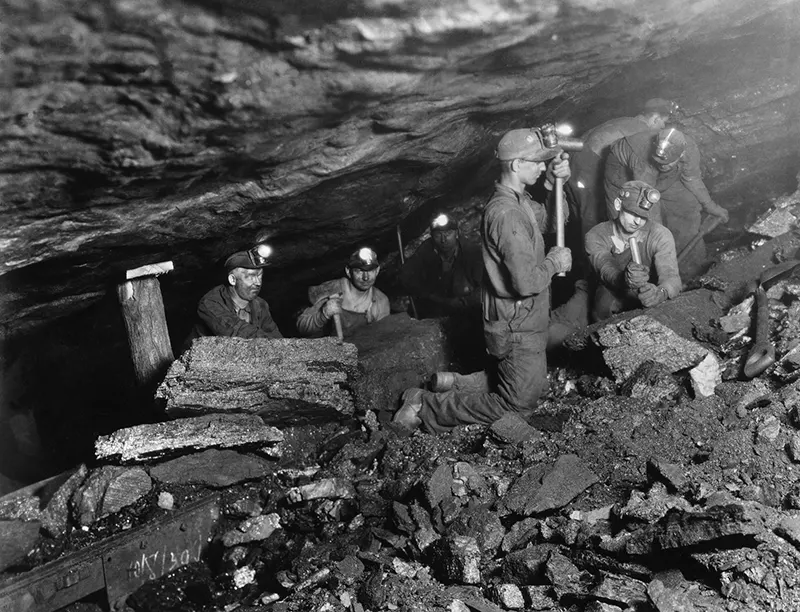

Miners with lamps on their helmets dig for coal.

Mining has always been especially dangerous, because of explosions, roof cave-ins, and the difficulty of underground rescue. The worst single disaster in British coal mining history was at Senghenydd in the South Wales coalfield.

On the morning of 14 October 1913 an explosion and subsequent fire killed 436 men and boys. Only 72 bodies were recovered. It followed a series of many extensive Mining accidents in the late 19th century, such as The Oaks explosion of 1866 and the Hartley Colliery Disaster of 1862.

Most of the explosions were caused by firedamp ignitions followed by coal dust explosions. At Hartley there was no explosion, but the miners entombed when the single shaft was blocked by a broken cast iron beam from the haulage engine. Deaths were mainly caused by carbon monoxide poisoning, known as afterdamp.

Coal miners in the 1910s.

Mitsubishi Hojyo coal mine disaster, occurred on 15 December 1914 at the Mitsubishi Hojyo coal mine located in the Kyushu Island of Japan. The disaster directly led to the deaths of 687, representing the worst mining incident in Japanese history.

The Courrières mine disaster, Europe’s worst mining accident, caused the death of 1,099 miners in Northern France on 10 March 1906.

As well as disasters directly affecting mines, there have been disasters attributable to the impact of mining on the surrounding landscapes and communities. The Aberfan disaster in 1966 buried a school in South Wales when a huge slag heap collapsed, killing 116 children and 28 adults.

Entrance to mine shaft in West Virginia, photographed by Lewis Wickes Hine in 1908.

Harry Fain loading coal that has just been shot from the face. He will load about 16-17 tons per day. Inland Steel Company, Wheelwright Mines, Wheelwright, Floyd County, Kentucky. 1940s.

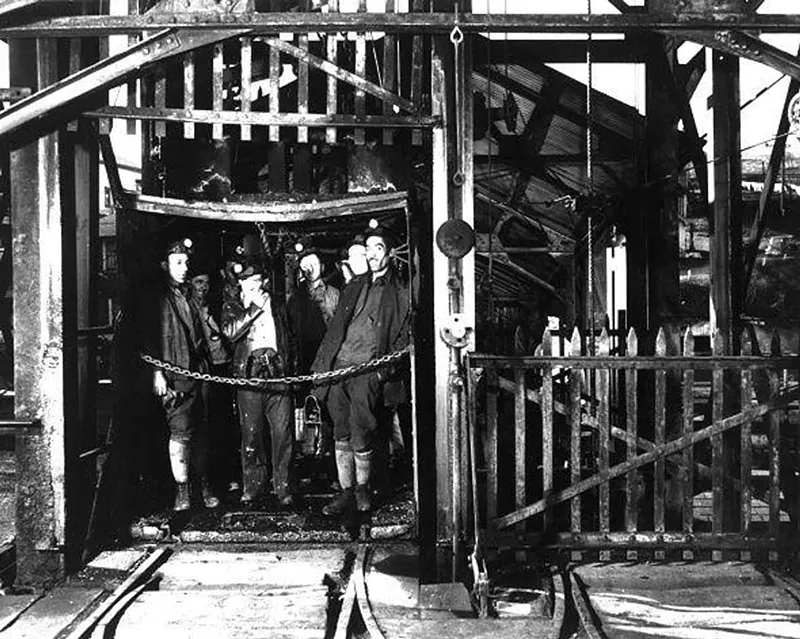

Coal miners ready for the next shift in Maidsville, West Virginia in 1938.

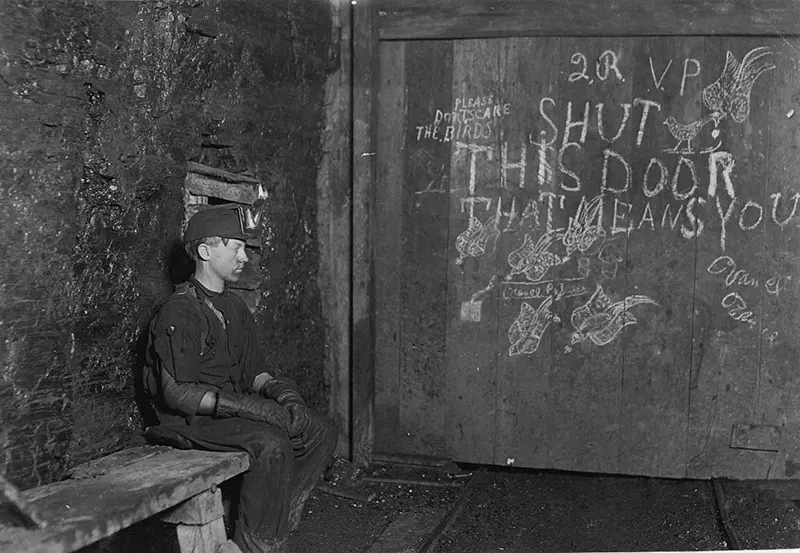

“Vance, a Trapper Boy, 15 years old. He is trapped for several years in a West Va. Coal mine. $.75 a day for 10 hours work. All he does is to open and shut this door: most of the time he sits here idle, waiting for the cars to come. On account of the intense darkness in the mine, the hieroglyphics on the door were not visible until plate was developed.” Photo by L. Hine. (More photos of child miners).

These miners, known as “Bevin Boys,” worked in the Markham Colliery, Yorkshire, England in 1943. Bevin Boys were young British men drafted into the coal mining industry after the start of the second World War.

This image was also taken with the Sashalite in 1930. These men are in a mine cage, used for moving men and supplies up and down from the mine.

Miners digging for coal in South Wales, 1931.

Miners going into the Slope, Hazelton, Pennsylvania.

Young coal mining boys before Child Labor laws in 1899.

A loaded coal train and the gravity incline at a coal mine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1907.

Miners in a cage ready to be lowered into the mine, Pennsylvania, 1942.

Clover Gap Mine, 1946. (Photo by Russell Lee).

December 1910: Young boys at work at the troughs used for cleaning coal at a pit in Bargoed, South Wales. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images).

Women and children scavenging for coal from slag heaps near closed mines during the coal strike. (Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images)

Two miners in an underground coal mine, 1920.

A bare-chested miner can be seen pushed a cart through Cook’s Kitchen Mine in Cornwall, as fellow miners operate the machinery, 1890s. (Photo by J.C. Burrow).

A bare-chested man works at a mining shaft, 1890s. (Photo by J.C. Burrow).

Miners clambered up rickety ladders and under the precarious timber beams holding the mine shaft together, Britain, 1890s. (Photo by J.C. Burrow).

In this frame, the miners can be seen boring into the rock. The tin and copper from the Cornish mines sold for millions across the world. (Photo by J.C. Burrow).

In this more relaxed picture the miners are seen at rest, as many of them eat Cornish pasties. (Photo by J.C. Burrow). 27: (Photo by J.C. Burrow).

(Photo by J.C. Burrow).

(Photo by J.C. Burrow).

Miners working in a gold mine at Gympie, Queensland. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland.

.jpg)

Coal miners boiling juice of sugarcane into sorghum molasses, West Virginia, 1938. (Photo by Marion Post Wolcott).

.jpg)

Coal miners ard gambling in the center of town, West Virginia, 1938. (Photo by Marion Post Wolcott).

.jpg)

Coal miner waiting to go home in friend’s truck, West Virginia, 1938. (Photo by Marion Post Wolcott).

.jpg)

Coal miner’s shack and some of his family, West Virginia, 1938. (Photo by Marion Post Wolcott).

.jpg)

Many miners’ families live on riverboats, in West Virginia, 1938. (Photo by Marion Post Wolcott).

.jpg)

Children of riverboat family. (Photo by Marion Post Wolcott).