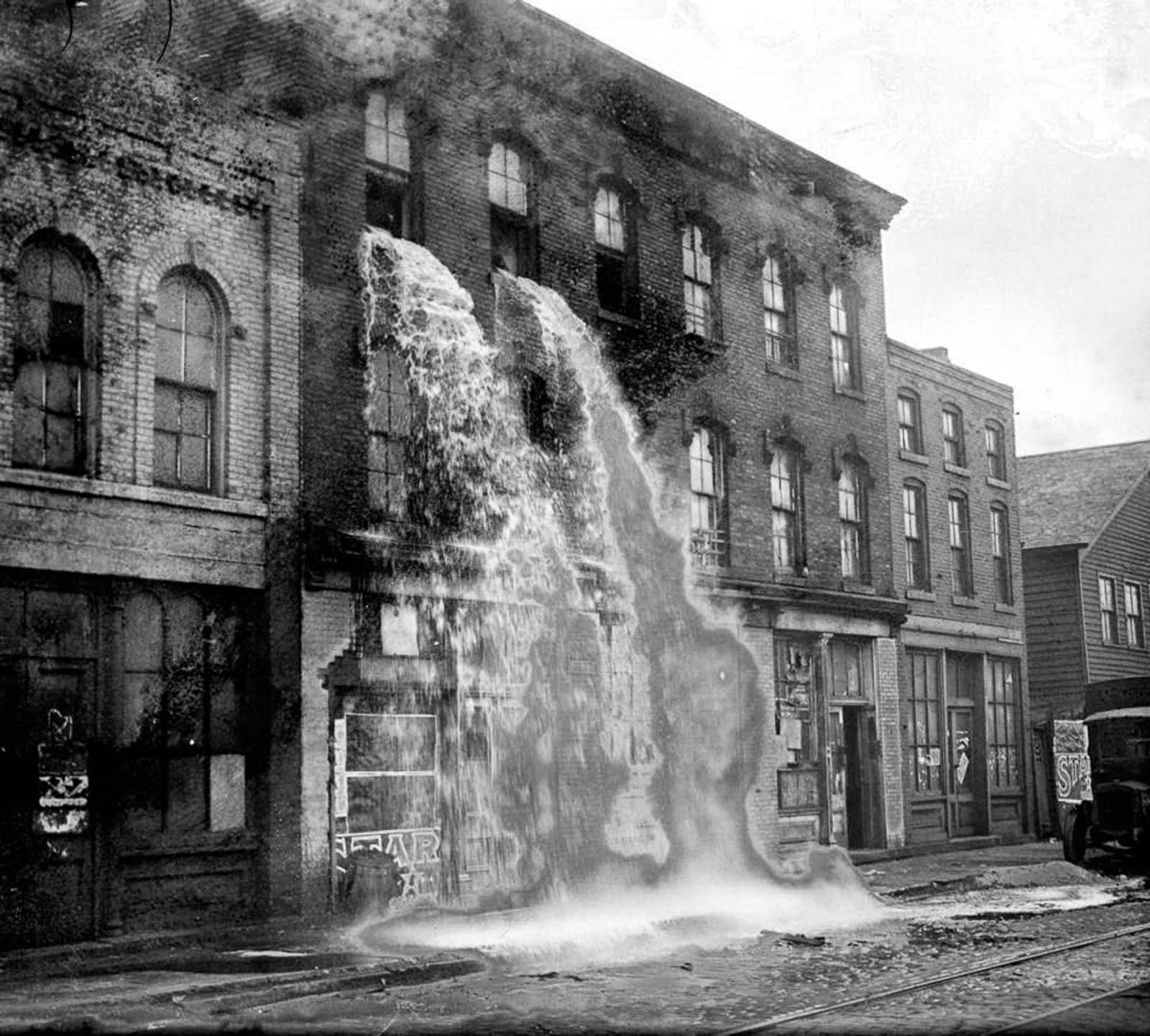

Prohibition agents dump liquor out of a raided building, 1929.

Prohibition was the attempt to outlaw the production and consumption of alcohol in the United States. The call for prohibition began primarily as a religious movement in the early 19th century – the state of Maine passed the first state prohibition law in 1846, and the Prohibition Party was established in 1869.

The movement gained support in the 1880s and 1890s from social reformers who saw alcohol as the cause of poverty, industrial accidents, and the break-up of families; others associated alcohol with urban immigrant ghettos, criminality, and political corruption.

With America’s entry into the First World War in 1917, prohibition was linked to grain conservation. It was also aimed at brewers, many of whom were of German descent.

Limits on alcohol production were enacted first as a war measure in 1918, and prohibition became fully established with the ratification of the 18th Amendment in 1919 and its enforcement from January 1920 onward.

Described by Herbert Hoover, US president from 1929-1933, as “a great social and economic experiment”, prohibition had a considerable impact on American society before its repeal in 1933.

The 18th Amendment stipulated that you could not make, sell, or transport alcohol. Under the terms of the act, prohibition began on 17 January 1920.

The act defined ‘intoxicating liquor’ as anything that contained one-half of one percent alcohol by volume, but allowed the sale of alcohol for medicinal, sacramental, or industrial purposes.

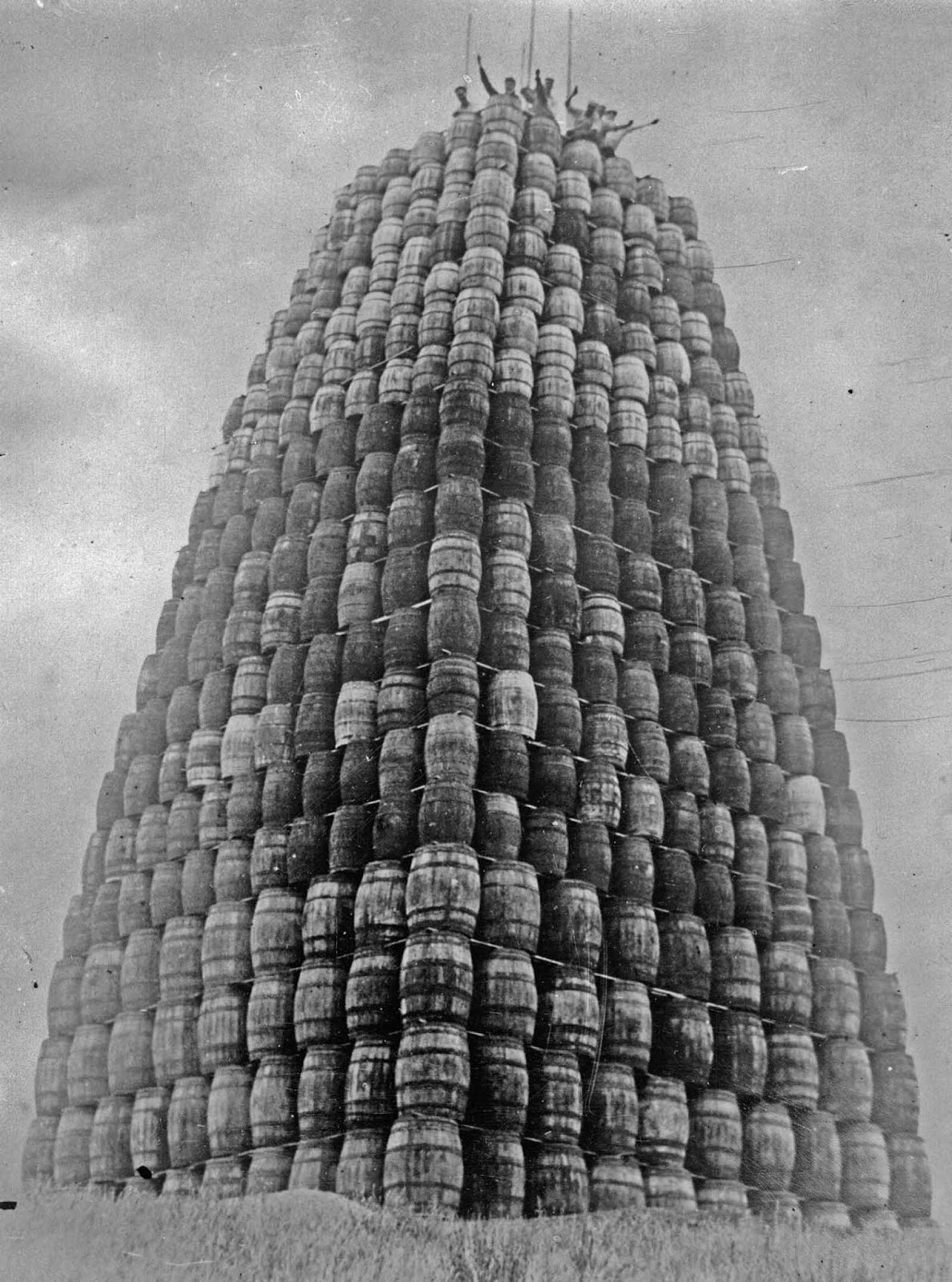

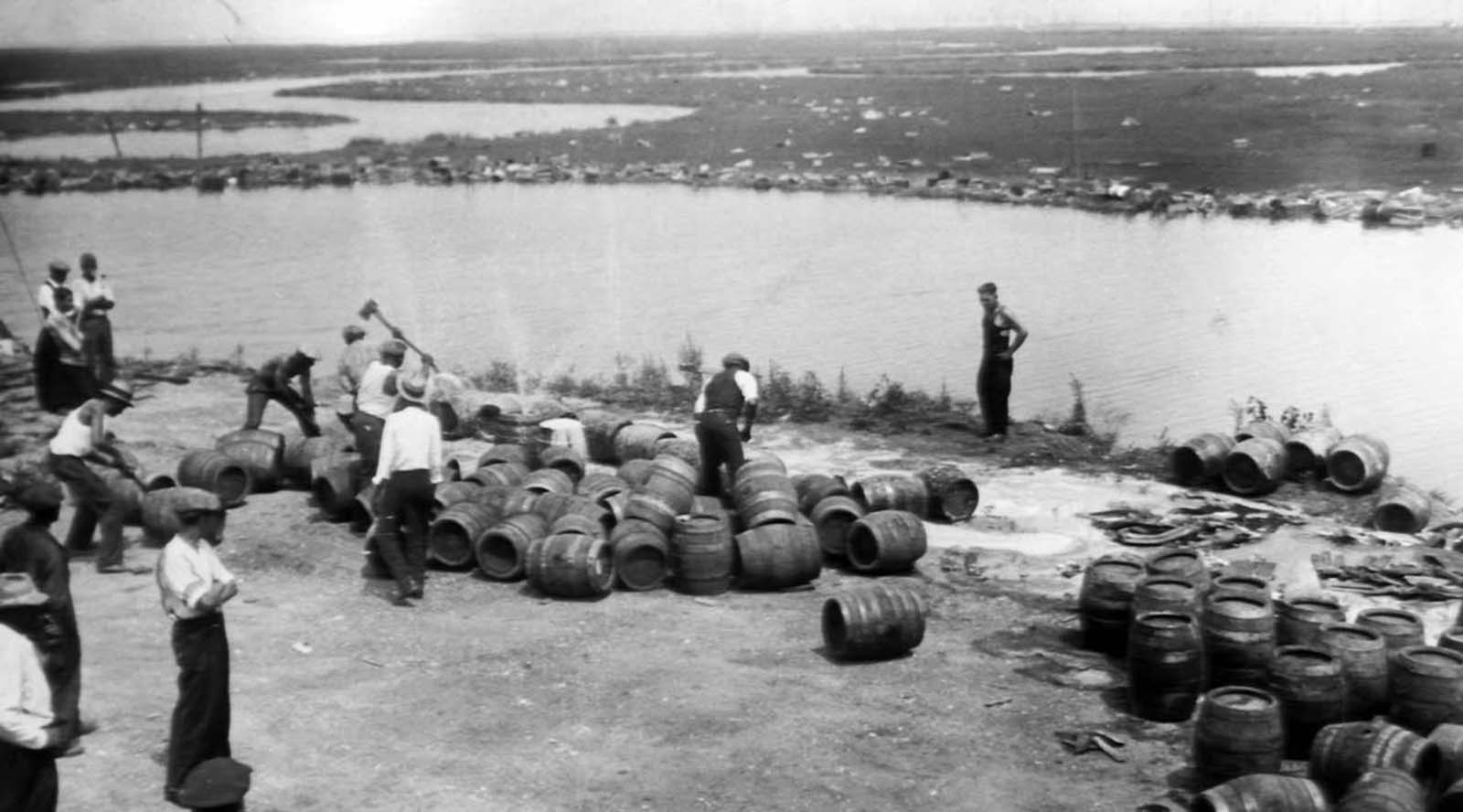

A tower built with barrels of alcohol, which will be destroyed later. 1929.

The private possession or consumption of alcohol itself was not itself illegal and, as many Americans continued to demand alcoholic beverages, criminals stepped in to meet the demand by illegitimate means.

Where previously there had been bars and saloons, there were now illegal drinking dens known as ‘speakeasies’ or ‘blind pigs’, which by the end of the decade were numbered at an estimated 200,000. People also took to producing their own illicit booze or ‘moonshine’, ‘bath-tub gin’, or home-brewed beer.

Enforcement of the legislation thus proved enormously difficult for local police forces and the federal Bureau of Prohibition, or Prohibition Unit.

The bureau numbered around 3,000 agents, who had to police the coastal frontier and land borders with Canada and Mexico to prevent smuggling, as well as investigate the illegal internal production and transportation of alcohol in the country as a whole.

During prohibition, the consumption of hard liquor (spirits) probably dropped by as much as 50 percent and other alcoholic beverages by about one-third.

As a result, it did have some positive effects: the number of deaths due to cirrhosis of the liver fell considerably but was offset to some extent by deaths caused by drinking adulterated alcohol.

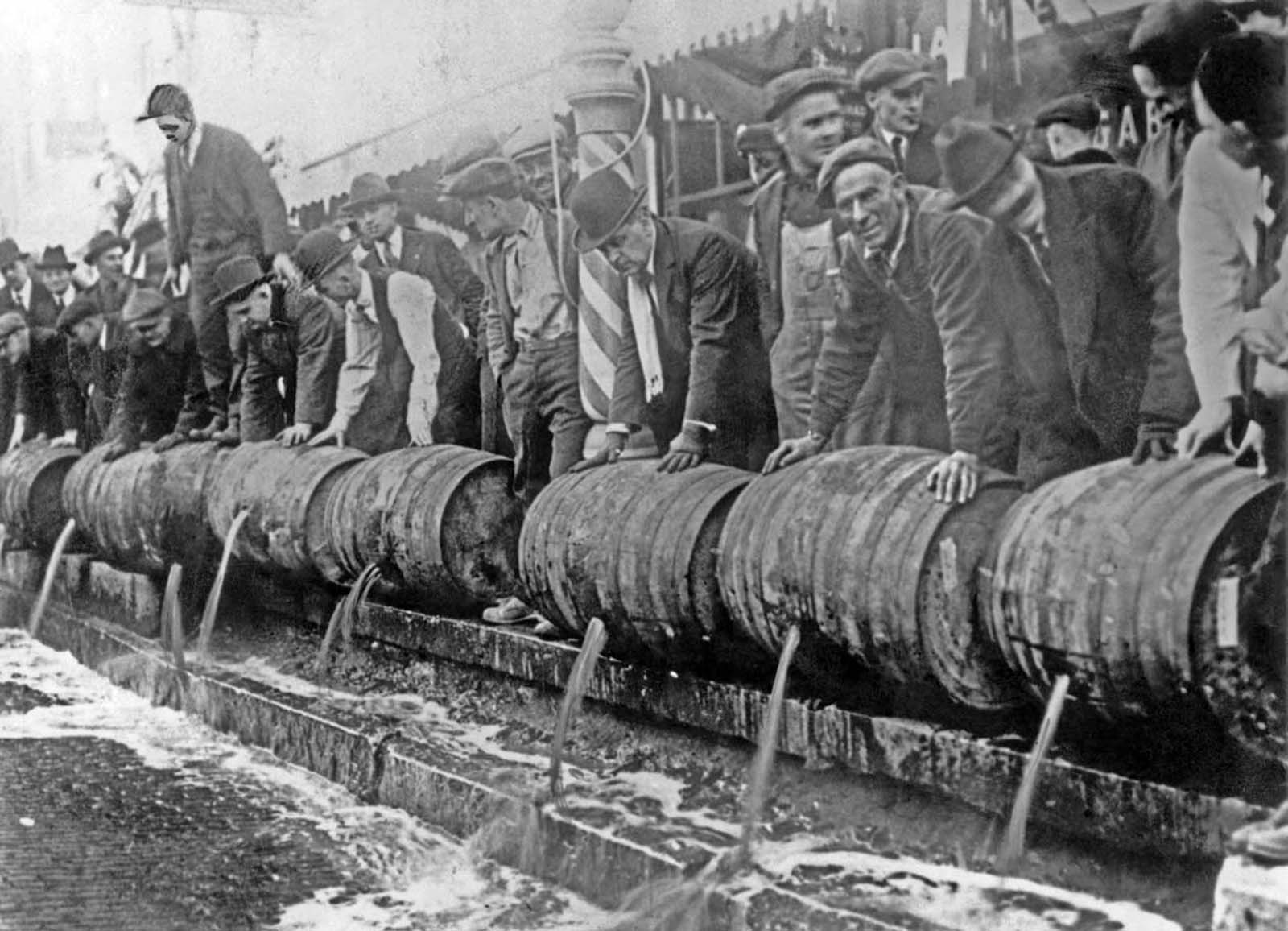

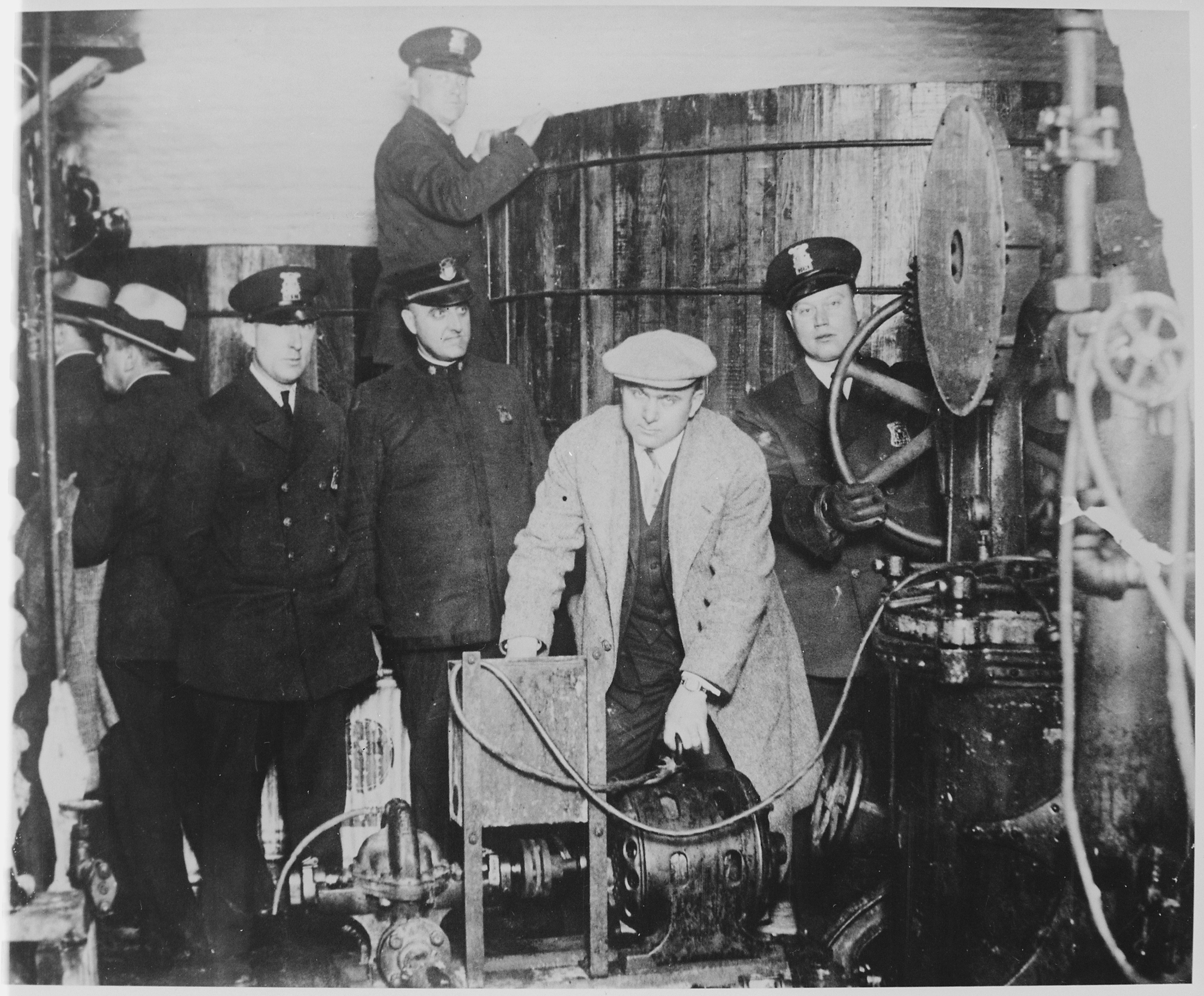

An FBI Officer breaks a confiscated barrel of beer. 1924.

However, in 1929 Mabel Walker Willebrandt, the former Assistant US Attorney General who had headed prohibition prosecutions, conceded that alcohol could be purchased “at almost any hour of the day or night, either in rural districts, the smaller towns, or the cities.”

At the same time prohibition almost completely destroyed the brewing industry, causing a huge loss in jobs. It also resulted in a loss of $11bn in tax revenues, and cost $300m to enforce.

Passed in February 1933 and ratified on 5 December 1933, the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th and so ended prohibition in the United States.

Control of alcohol after 1933 became a state rather than a federal issue. A small number of states remained ‘dry’ for some years – Mississippi was the last until 1966, but there are still local areas where the ban on alcohol remains.

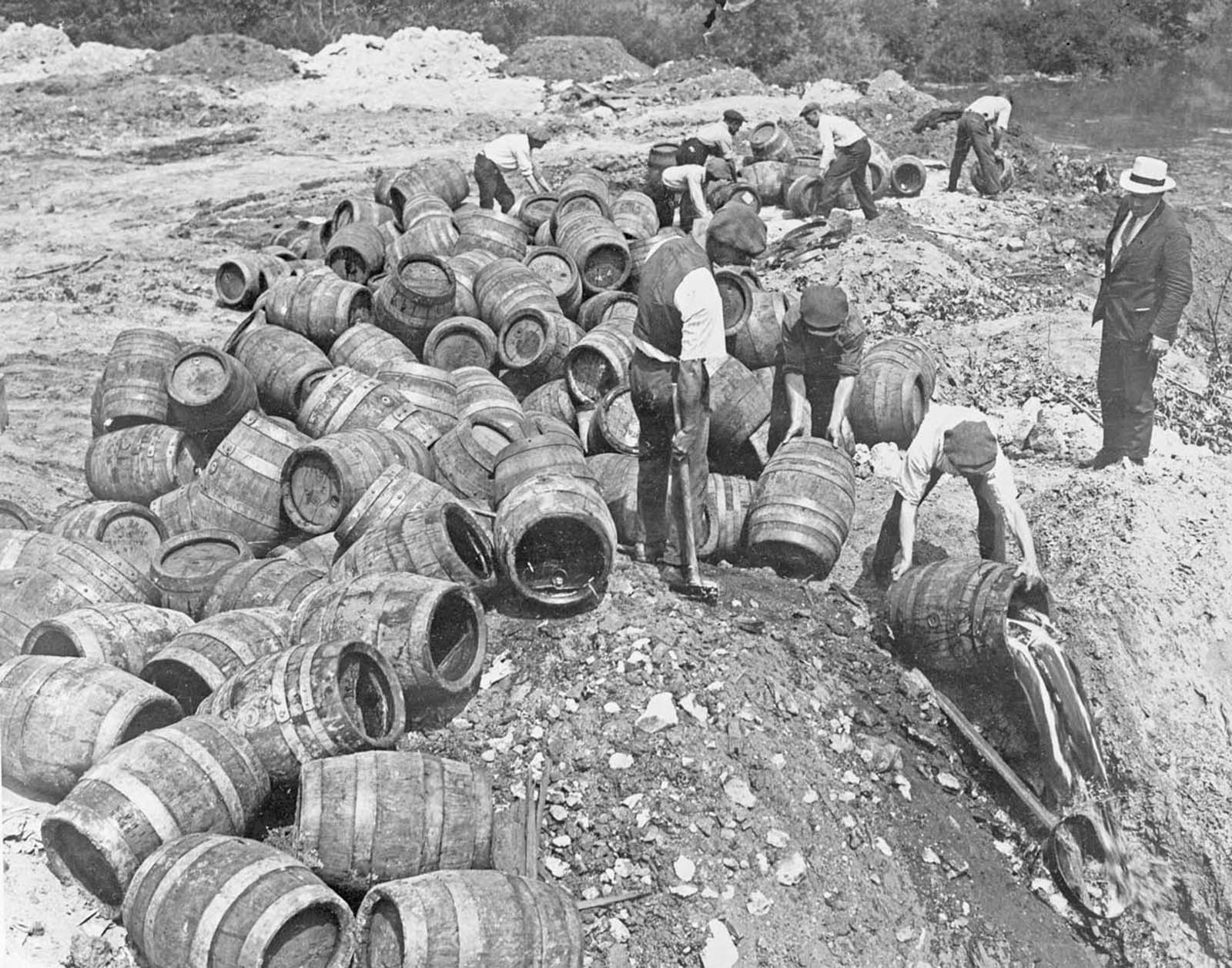

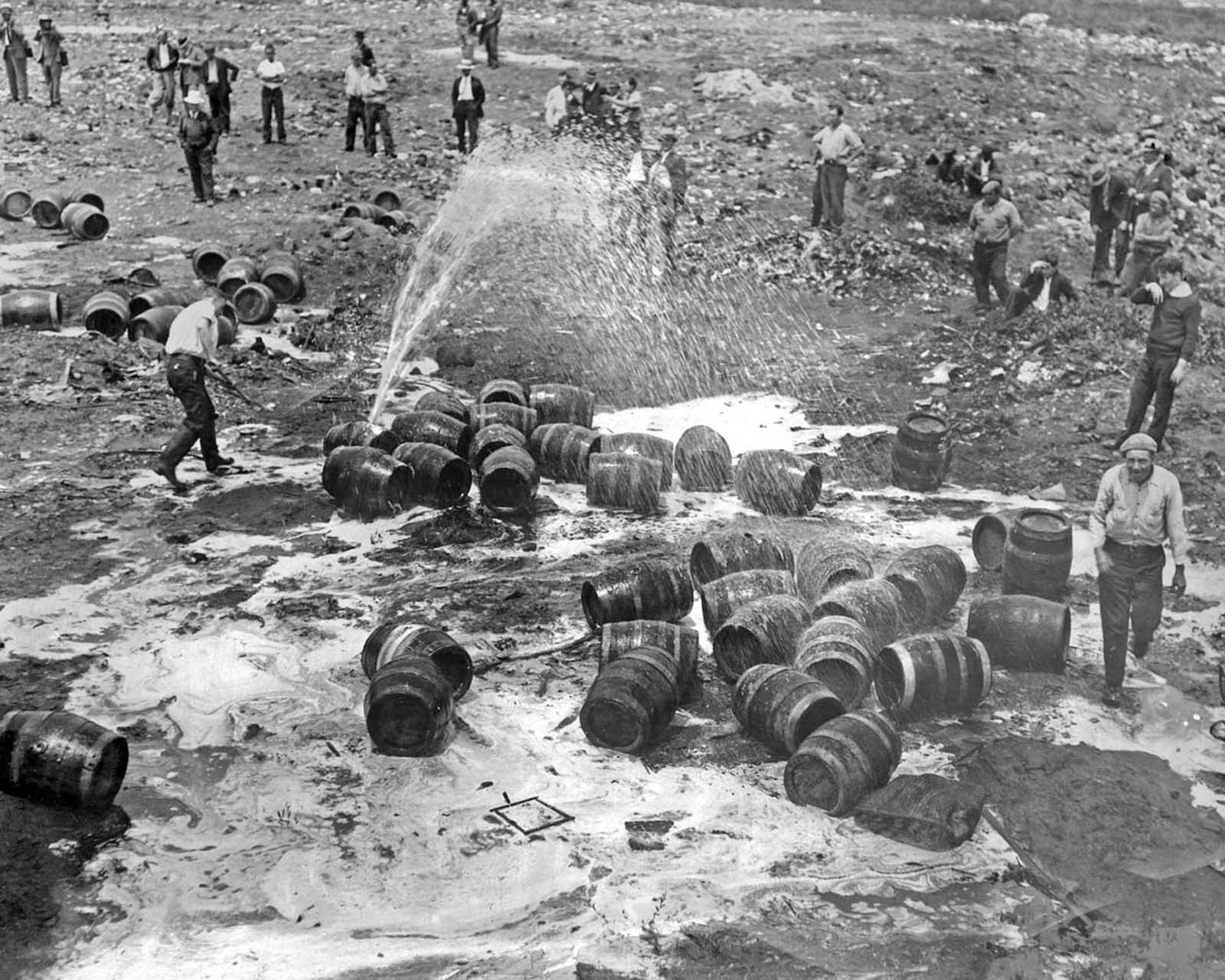

Barrels of beer emptied into the sewer by authorities during prohibition.

Emptying more than a hundred kegs of beer seized in a raid.

A brewery in Washington, DC, switches from brewing beer to making ice cream during Prohibition. Workers roll the giant beer vats out to make room for ice cream production equipment.

Police dumping beer from barrels into sand at Atlantic City.

Prohibition agents destroy unlawful liquor seized in Hoboken.

Two carloads of beer poured into the Hudson River.

At an army base in Brooklyn, men drain 10,000 barrels of beer into New York Harbor.

Two men pour alcohol down a drain during prohibition in the United States, c. 1920.

Prohibition-era policemen Moe Smith (on the left in top picture, on the right on the bottom picture) and Izzy Einstein (on the right in the top picture, on the left in the bottom picture). The pair would use disguises to infiltrate speakeasies.

Police mug shot of Chicago mobster Al Capone, one of the leading gangsters of the prohibition era.

A potential customer examines an advertisement for an illegal drinking den or speakeasy during US prohibition in the 1920s.

Detroit police in a clandestine brewery during the Prohibition era.

Orange County, California, sheriff’s deputies dumping illegal alcohol, 1932.

Americans celebrated the end of Prohibition in 1933.

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / National Archives / Wikimedia Commons / Hulton-Deutsch Collection / Corbis).